Contagious Ideas

How songs, ideas, and movements spread

When Laney Griner took a photo of her 11-month-old son at the beach, she had no idea he would become an internet sensation. The baby was clutching a fistful of sand with his face scrunched into an adorable grimace. He was simply doing what babies do.

But once Laney shared the photo online, it became a wildly popular meme known as Success Kid. “There was no getting the picture back,” Laney told Buzzfeed. “The internet had it.” Success Kid blew up – the meme appeared in a Superbowl ad, on newsstands, and even on billboards. The meme was used to illustrate success achieved against the odds. “And that warmed my heart,” Laney said, revealing that her son, Sam, was born prematurely and had brain surgery at six weeks old. “I felt like that was the most appropriate title for him, and it was given to him by the internet.”

The scientist Richard Dawkins coined the term “meme” in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene, using it as a way to describe how ideas, behaviors, songs, or other cultural elements spread from person to person, kind of like a virus. Dawkins writes:

“Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain…”

Sociologist Damon Centola studies how this leaping process happens. The idea of genes passing on through the generations, or a virus jumping from one body to another, is often seen as the main way that ideas spread. But Damon says the story is a little more complicated. He makes a distinction between what he calls “simple contagions” and “complex contagions.” Success Baby is an example of the former – you see it, it’s great, you want to share it. A complex contagion, on the other hand, takes a bit more convincing. It spreads, but it may take a while for it to build momentum and catch on. “This includes novel technologies like Twitter and Facebook, but also social movements like Black Lives Matter, Arab Spring, and the Civil Rights movement,” Damon says.

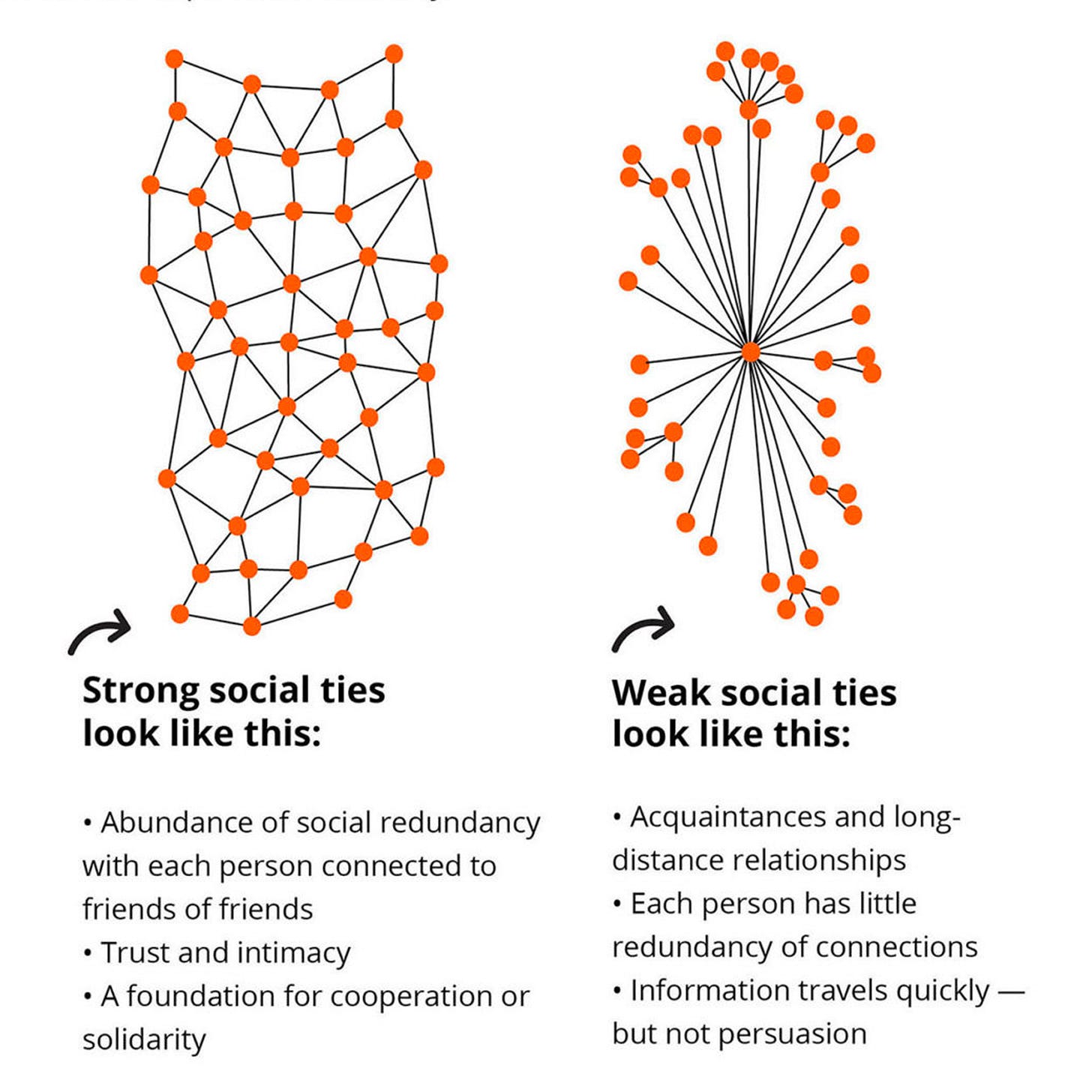

Complex contagions rely on what sociologist Mark Granovetter calls “strong ties.” That is, connections within a tight network of family and close friends. This is opposed to weak ties, which are more like casual relationships with acquaintances.

Weak ties are useful for quickly spreading information – or adorable memes. But social and behavioral change rely on networks with strong ties. Before we join a movement, adopt new technology, or agree with an idea, we first need to see that the people we’re closest to are on board with it. “For simple contagion to spread, all it takes is contact with one person,” Damon tells us. “For a complex contagion, you need to be convinced.”

ON THE PODCAST

March 1: Why do some companies become household names, while others flame out? How do certain memes go viral? And why do some social movements take off and spread, while others fizzle? This week, we look at how movements spread – and how social contagion can be harnessed to build a better world.

March 8: For generations, living openly as a gay person in the United States was difficult, and often dangerous. But there’s been a dramatic change in public attitudes toward gay people. This week, we explore one of the most striking transformations of public attitude ever recorded. And we consider whether the strategies used by gay rights activists hold lessons for other groups seeking change.

WE ASKED…

Sociologists have found that trends and social movements typically always start small, not with influencers but with ordinary people. Is there a trend or an idea *you* loved before it got big?

FROM THE TWITTERATI

WHAT SHANKAR IS READING

Why is Covid so much worse in some countries than in others?

The end game for politicians these days? Becoming content creators.

Covid differential impacts on essential vs non-essential workers:

A MOMENT OF JOY

Speaking of babies…

Another moment of joy for us here at Hidden Brain -- we’re thrilled to share that you can now grab a copy of Shankar’s new book, co-authored with Bill Mesler. It’s called Useful Delusions: The Power and Paradox of the Self-Deceiving Brain. And if you’d like to attend one of Shankar’s upcoming (virtual) book talks, you can find information about those at the same link.